For a science-fiction group, we try to incorporate a decent bit of realism in to the dynamics of what might actually happen in a space battle. We've discussed all manner of strategies, debated tactics and vessel construction, and now I (Moffatt) occasionally try to simulate what might actually happen.

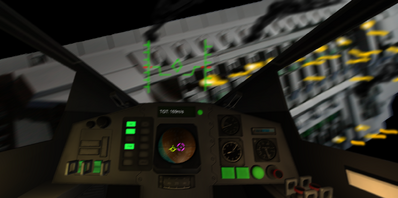

If you see this, you're almost certainly dead.

Just for some background, I don't pretend to be an expert on all of this stuff, but I plan to be for a career. If I'm not doodling rockets in my engineering notebooks, I'm flying lunar missions in Orbiter 2010 or messing around in Kerbal Space Program (which I totally heard about first and was landing on the moon in Alpha with nothing but decouplers and fins before you even knew what the word "retrograde" meant). You might also catch me watching rocket launches and reading Von Braun and Goddard's work. I put a good amount of thought in to how an effective battle might pan out.

The Very Basics[]

I'll give you a ridiculously fast crash-course in orbital dynamics here. The secret to orbiting a planet is to fall and miss - that is to be travelling so fast that you're already past the ground you're about to hit. Think of it like jumping off a cliff over some rocks before you hit water. You fall PAST the rocks because your sideways speed is enough to get you over while you fall. Orbit is a constant state of falling and missing around a planet.

This means you need to go VERY FAST to stay up (for Earth anyway). For example, the International Space Station travels at about 7km/s and it's 370km up. To get only a four-hour drive away from the planet, you need to travel 7 km in the time it takes to say "kilometers". Consequently, you need a lot of gas to get up to that altitude and then get going sideways too.

Important Note: Assuming you have a perfectly round orbit (not exactly common, but ideal) then you will always stay the same speed, and everything else at the same altitude will also have the same speed (if not direction). This will come up next

I'll likely add to this section as I remember things.

Intercepting a Target[]

In orbit, there are, for simplicity's sake, 3 ways of approaching your target:

1)Head-on*

2)From the side

3)From behind*

- By Head-On I mean approaching in pretty much the opposite direction of their orbit. For instance, if the target moves 7 m/s west, I move 7m/s east. Similarly From Behind means I approach with a relatively similar velocity to my target, though technically I could be ahead of it while slowing down. This just means that I'm going west along with my target

Head-On[]

In a combat scenario, this is probably the highest risk/reward strategy. You've got a relatively short time to aim and correct, but if you manage to hit your target you will do some serious damage. To put this in perspective, if I'm going 7km/s towards a target going 7km/s in the opposite direction, I could throw a shoe out the front of my spacecraft and literally rip the target in half. At these ludicrous speeds, you need an insane amount of armor to risk the enemy getting a shot off at you. I imagine the giant Coalition space-cathedrals would really have no issue with this strategy.

I figure your best bet here would be to just dump flak in the direction of the target - aim isn't so much of an issue and a little piece that managed to impact can still seriously mess up a target. Actually, that impact in the link is a one gram object at 7 km/s in to aluminum. I was talking about a relative speed of 14, so my situation would be even more damaging.

From the Side[]

This is a happy medium of HOLYSHITFAST and time to get your aim in. It's also the most likely way you're going to intercept a target, because you can't reasonably expect to perfectly match a target's heading - especially from a ground-launched interceptor - within time and fuel constraints. If you're perfectly perpendicular to your targets path and manage to have relatively little distance between you at your closest intersection, (I'll again stick with the Low Earth Orbit scenario at ISS level) then your relative speed to the target will be the square root of twice your velocity squared - add the velocity of you and the target with vectors to get your net velocity. Here it's a little harder to aim your flak guns, but it's at the point where a good computer might be able put put a missile near the right place to do some damage.

From Behind[]

This is most like any space battle you see in the movies. There's a slow build up, so everyone knows it's coming (This is also a terrible disadvantage. I think space battles would wind up like medieval battles where nobody really wanted to commit unless they were absolutely sure they would win.) The sexiest part about this sort of stratecgy is that when your velocity relative to your target is small, you can use missiles and cannons with relative ease. These engagements are the spectacular cinematics where you can really beat the everloving cupcakes out of your opponant. This is also really the only range where short range fighter-bombers are effective, so I've learned. More on that later. The real advantage to this is that you actually have the chance to evade your enemy's fire while still laying on the pain, and you don't have to worry about little, impossible-to-dodge flecks of paint tearing massive gashes in your pressure hull.

A Study in Interception[]

Admittedly, this is nothing I haven't done dozens of times before, but for the benefit of the rest of you, here's the "From Behind" approach.

Set up

Here's the deal - I threw together a really simple orbiter and put it in to orbit at 256km above Kerbin because it seemed like a fun number. Note that Kerbin is smaller than Earth, but the gravity field is the same. This means that I don't have to go as fast as I would in real life, since around Earth I would be going well over 8km/s in stead of 2.

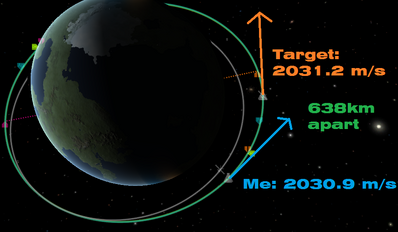

Now, I have about 638km to catch up to my target, but how should I do that when we're going almost the exact same speed?

Retroburn!

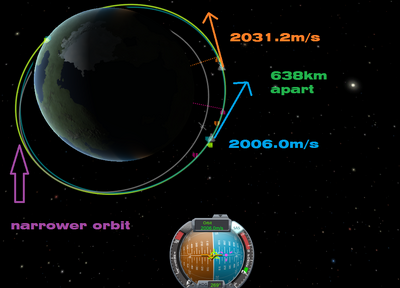

Counter-intuitively, the answer is to slow down. All I did was point the rocket in the opposite direction of travel and burn off a few meters per second. If I was pressed for time, I could easily have burned off a much greater speed, but then I also have to burn it back when I get close to the target. A capital ship full of gas shouldn't have a problem with intercepting a target within an hour and a half.

Notice how this change in energy means that the opposite side of my orbit shrinks. This means that my total distance to cover shrinks considerably, even if my speed is less.

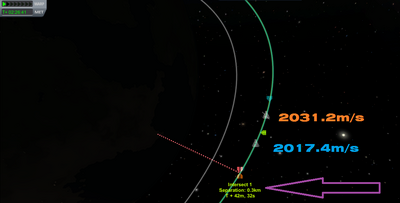

Getting close

I caught up slowly for two orbits and then did a little prograde (forward) burn to make sure my next intercept would be very close to the target. This is actually in the "stupid-close" range where you don't want to be next to a Coalition ship.

I'll also note that, though my distance will be close to zero, my relative speed to the target at the intercept may not be. I took it slow so I didn't have to correctively burn for a long time near the intercept range.

Right there

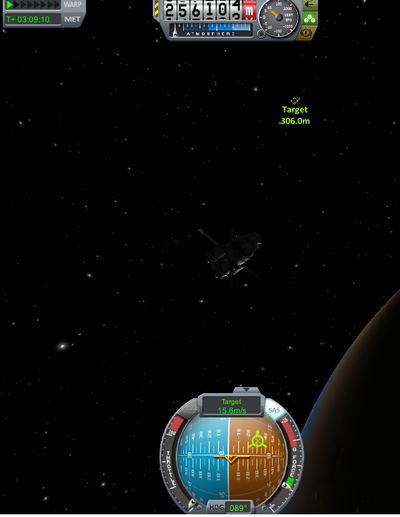

Here is my orbiter with the target (identical vessel) highlited 306m away. As you can see by the mission timer, it took 3 hours 10 minutes to get here, but I was working by hand and was playing it safe. Even this ship could easily have caught up in a single orbit, had I timed everything right. For the record, 15.6m/s is 56km/h or 35mph. I then opted to slow down just for fun since I didn't have any missiles to lob at the target.

It's also worth noting that if you match the velocity of the target here you will stay in orbit with it without much trouble. So, if you feel like a long, protracted battle then this is your strategy.

I think that UNE craft would try to hang back by about 2-10km and just dump missiles.

Shadow

As a basic summary, each tactic has its own different risks and rewards, so you should choose what you feel best suits your ship/fleet.

I imagine the Coalition with the MAPDs and walls of turrets would prefer the head-on charge, relying on their armored prow to take the brunt of anything thrown at them.

Earth's navy with it's love of missiles would wind up attacking from behind in the ideal situation. Especially since any ground-launched reinforcements have the chance to get a head start in the right direction, they also have the home-field advantage of knowing where the Coalition is and where they're going.

There's also the definite possibility of firing projectiles or missiles from around the planet that will intercept the target at a later point. This is theoretically possible, but the odds of your target moving are good and nobody wins with flak whizzing about every which way. I haven't gotten around to doing any math/simulations for this attack scenario. Yet.

On Starfighters[]

Oh boy, do we have fun with this one. After a lot of debate, we've decided that low-orbit, station/carrier based starfighters are worth it, as well as ground launched interceptors. For deep space and higher orbit altutudes, a small craft simply doesn't have the delta-v budget to be effective and make it home.

I've now conducted two tests on starfighter design and use - The first was a generic X-Wing type thing in Kerbal Space Program just to get an idea of how much gas it would take to lug something to orbit, how much gas you would need to maneuver, and whether it was at all possible in a compact package.

My first starfighter separates from the orbital booster stage.

This here is my first, unnamed starfighter. The wings were meant for a possible re-entry test, but that all went to pot when I ripped one of them off as I clipped my target. Don't eat and pilot.

This basic proving flight showed me a few things:

1)You can maneuver a fighter with relative ease as long as your relative speed is near that of your target

2)Guided missiles are your friend. If your target is in cannon range, SO ARE YOU!

3) I just thought of something - fighters are a good way to make sure a target's defenses are being spread out over its entirety. If I'm firing at a cruiser from my own cruiser, then it only has to pump out countermeasures in one direction. When assailed from all sides, its defenses would be substantially thinned

4)Give your pilots a parachute, just in case

It's also worth noting that this had enough fuel to modify it's orbit within about 30 degrees. There's no way it could pack the gas to turn all the way around and stay in orbit.

Fire 3!

My second attempt was based on a more realistic design. Sandwiched between two boosters, it finalized an orbit of 300km with gas to spare. I should mention that this booster stage had far less fuel than the previous fighter, because launching a Saturn V every time you need a figther up gets inconvenient. This design was bulkier than it would actually be in real life since I really wanted to get some missles going in the limited realm of KSP.

What I learned:

1)Fighters just can't attack head on with much effectiveness. They'd be shredded and just don't pack adequate punch for the engagement time. Maybe, MAYBE you could deploy from a carrier, zip by, and get back in the carrier after. Maybe.

2) Try to balance the best possivle acceleration with fuel efficiency. My nuclear engines were super efficient, but took a long time to get going.

Starfighters II: Carrier Based Operations[]

Back for another installment because I have four midterms coming up so what else would I be doing? [1]